We put three castors to the test

Why buying Australian-made Fallshaw wheels and castors will save you time and money.

When buying castors and wheels, it can be tempting to choose the cheapest option—with the idea that all castors are the same ... but are they?

Not all castors are designed and manufactured to go the distance. Reasons why:

Cheaper alternatives do not always adhere to ISO testing standards and may not be suitable for abusive environments. (For example castors on linen trolleys are frequently moved and lifted on-and-off trucks and over various surface types 24/7).

Buying cheaper alternatives can reduce the upfront cost, but in the long term this can result in ongoing expenses and lost time. For example, replacing broken castors on a fleet of trolleys, will result in replacing castors more often, and will be costly to replace over the longer term.

Advertised load ratings can vary between suppliers. Some companies only advertise static load ratings, whereas Fallshaw only advertise dynamic load ratings. (Dynamic load ratings refer to when the load is being moved, whereas static load ratings refer to when the load is still). This can be misleading because static load ratings are always lower than dynamic load ratings.

We want to help you to make an informed decision when it comes to buying best-quality products, so you don’t have to keep buying castors over and over again, nor be inconvenienced by having to replace broken castors, so we decided to put three castors to the test.

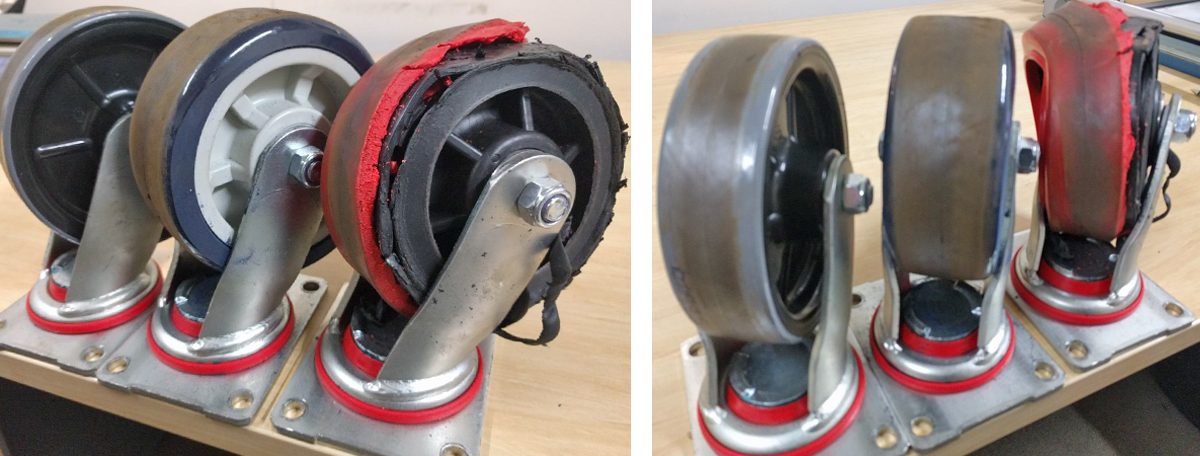

Pictured (from left to right): Fallshaw (Australian-made), EHI and QHDC castors (both imported).

Pictured (from left to right): Fallshaw (Australian-made), EHI and QHDC castors (both imported).

What we tested

In October we conducted rigorous performance tests of three similar castors – a Fallshaw castor (O Series HUR150/HZP), and equivalent castors from EHI and QHDC (both imported).

To see if each met Australian Standards (AS1961.2004) or International Standards (ISO22883:2004), a Dynamic Test was performed.

The objective of this test was to establish an operational load capacity at 4 km/hour, while establishing the maximum load which could be carried, while not showing functional impairment to the castor.

A breakdown of the Dynamic Test:

-

A speed of 1.1 metres per sec (4 km per hour).

-

Traveling over 4 mm bumps.

-

Traveling for 3 min in an anticlockwise direction, then alternating to a clockwise direction for 3 minutes (and alternating after each 3 minute cycle for the duration of the test).

-

Carrying a 450 kg load.

-

Traveling over a series of x 500 bumps.

-

A maximum 15,000 revolutions of the wheel (with no bumps).

What we discovered

Fallshaw (base)

Castor tested: O Series HUR (polyurethane on nylon, roller bearing) with a swivel plate fork.

The Fallshaw sample completed the test and successfully passed.

There were no signs of failure with the tyre and centre bonding. This is due to Fallshaw’s manufacturing method of the wheel, and the choice of materials used. For example, when the urethane tyre is manufactured, the nylon 6 material is injection-moulded into the tyre while under pressure. Due to the high temperature, the centre bonds to the tyre in a 'chemical type' lock—providing maximum strength and durability.

QHDC (imported castor)

After the castor completed the 500 bumps, the tyre started to separate from centre.

This indicates a failure of the bonding between the tyre and the centre.

The castor displayed runout after 500 bumps and about 5000 revolutions of the wheel (with no bump).

After 600 bumps and around 1407 revolutions of the wheel would be classed as failed. This can still however be used—but it would be borderline.

The castor completed the test during which time, the tyre flattened due to bonding failure on the centre. (From new 51 mm to 59mm after test).

Pictured: The tyre has spread over the centre.

Pictured: The tyre has spread over the centre.

EHI (imported castor)

The castor completely failed at only 208 cycles into the 500 bump test. The bonding failed between tyre and centre, and bearing hub (centre) failed.

Pictured: The tyre has detached from the centre.

Pictured: The tyre has detached from the centre.

Conclusion

Under identical test conditions, the Fallshaw wheel outperformed both QHDC and EHI wheels.

The materials and manufacturing process plays an important role in determining reliability.

Fallshaw’s manufacturing process (bonding of the chemical lock-to-centre) and selection of materials (virgin urethane and a virgin nylon 6 centre) result in a superior product. This is also backed up with a three-year warranty.

The materials used by both imported brands consist of a polypropylene centre (which is about half the strength of nylon), and a urethane tyre. The manufacturing process used on the poly centre have proven to be made with a mechanical lock-to-centre—which failed the test.

Pictured (from left to right): Fallshaw, QHDC, EHI castors after the test.

Pictured (from left to right): Fallshaw, QHDC, EHI castors after the test.